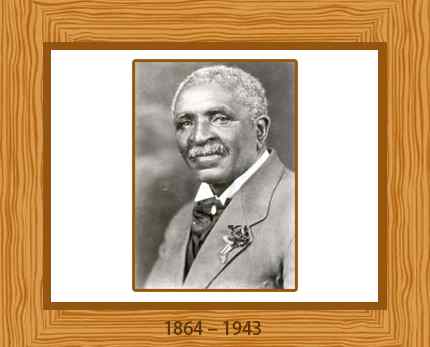

George Washington Carver was an American agricultural chemist, agronomist and botanist who developed various products from peanuts, sweet potatoes and soy-beans that radically changed the agricultural economy of the United States. A son of a slave woman, George won several awards for his brilliant contributions, such as the Spingarn Medal of the NAACP. He spent most of his career teaching and conducting research at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Tuskegee, Alabama.

African-American educator and agricultural researcher George Washington Carver (c. 1864-1943) grew up in Missouri with the white family that originally kept his mother as a slave. After earning his master's degree in agriculture from Iowa State College in 1896, he headed the agricultural department at Booker T. Washington's all-black Tuskegee Institute for nearly 20 years. Carver's research and innovative educational programs were aimed at inducing farmers to replace expensive commodities, and he developed a variety of uses for crops such as cow peas, sweet potatoes and peanuts. Carver had abandoned both teaching and agricultural plot work by the late 1920s, though he continued to advise farmers and students.

Carver was one of the best-known African-Americans of his era. Growing mainly from his research on peanuts, his rise to fame created myths and obscured much of the true nature of his work. His humble origins were part of his appeal to publicists who made him a national folk hero. He was born in the Missouri town of Diamond. His mother and older brother were the only slaves of Moses and Susan Carver, successful, small-scale farmers. His mother disappeared, presumed kidnapped by slave raiders, while George was an infant. He became both free and orphaned at about the same time.

The childless Carvers raised him and his brother as their own children. Being a sickly child, George was not required to do hard labor but helped around the house. Very early his intellect and knowledge of nature awed those around him, but he was not allowed to attend the neighborhood school because of his color. Thus at a young age he began a series of moves through the Midwest, seeking more education. He supported himself cooking, doing laundry, and homesteading before finally enrolling at Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa, in 1890.

At Simpson Carver majored in art, but a teacher convinced him to transfer to Iowa State College to study agriculture. By the time he completed a master's degree in agriculture in 1896, Carver had impressed the faculty as an extremely talented student in horticulture and mycology as well as a gifted teacher of freshman biology. Had he been white, he probably would have stayed at Iowa and concentrated on research in one of those fields. Instead he accepted an offer from Booker T. Washington to head the agricultural department at the all-black-staffed Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

For nearly twenty years (1896-1915) Carver labored in the shadow of Washington. He taught classes and operated the only all-black agricultural experiment station, but he proved inept at administration, provoking frequent clashes with the principal. He was engaged, however, in some of his most significant work–seeking solutions to the burden of debt and poverty that enmeshed landless black farmers.

Carver's research and innovative educational extension programs were aimed at inducing farmers to utilize available resources to replace expensive commodities. He published bulletins and gave demonstrations on such topics as using native clays for paints, increasing soil fertility without commercial fertilizers, and growing alternative crops along with the ubiquitous cotton. To enhance the attractiveness of such crops as cow peas, sweet potatoes, and peanuts, Carver developed a variety of uses for each. Peanuts especially appealed to him as an inexpensive source of protein that did not deplete the soil as much as cotton did.

Carver's work with peanuts drew the attention of a national growers' association, which invited him to testify at congressional tariff hearings in 1921. That testimony as well as several honors brought national publicity to the "Peanut Man." A wide variety of groups adopted the professor as a symbol of their causes, including religious groups, New South boosters, segregationists, and those working to improve race relations. Some white publicists exploited Carver's humble demeanor and apolitical posture to provide a "safe" symbol of black advancement; many, however, seem to have been genuinely captivated by his compelling personality. Carver's fame increased and led to numerous speaking engagements, taking him away from campus frequently.

By the late 1920s Carver had abandoned both teaching and agricultural plot work. He continued to advise peanut producers and others, always refusing to accept compensation. Much of his time was devoted to lecture tours of white college campuses, sponsored by the Commission on Interracial Cooperation and the ymca. With his warm personality he cultivated close personal relationships with dozens of young whites, opening their eyes to racial injustice, and continued to serve as a mentor and father figure to black students.

Carver never made a significant contribution to scientific theory, and he developed no commercially feasible new products. His ideas of sustainable agriculture based on renewable resources were out of step with his times, but perhaps not with the future. His early work enriched the lives of countless sharecroppers, and later in life he was a potent source of inspiration as a symbol of African-American achievement.

Gary R. Kremer, George Washington Carver in His Own Words (1987); Linda O. McMurry, George Washington Carver: Scientist and Symbol (1981).

The Reader's Companion to American History. Eric Foner and John A. Garraty, Editors. Copyright © 1991 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

www.history.com