DEAD RECKONING - THE POLLUX-TRUXTON DISASTER

Lanier Phillips was born on March 14, 1923 in the rural American town of Lithonia, Georgia. The great-grandson of slaves, Phillips grew up in a time and place where racism was still shockingly prevalent. The local government did not fund schools for black children and would not allow them to attend class with white students. The Ku Klux Klan was active and influential, with a membership that included policemen, shopkeepers, and other prominent residents. As a boy, Phillips saw Klansmen parade through town every Saturday night and terrorize its African-American residents - they fired guns into the air, dragged black men out of their homes, and beat them in front of their families. When local African-American parents built a school for their children, the KKK burned it to the ground. All of this instilled a deep and lingering fear in Phillips and damaged his sense of self-worth. "I saw no future, I had no dreams," he once said of his childhood.1

Phillips grew up assuming he would one day become a sharecropper like his parents, but this was not the case. In 1941, America entered the Second World War and Phillips decided to join the Navy. He completed boot camp when he was 18 years old and was assigned to the destroyer USS Truxtun. Military service, however, did little to improve his prospects. The US Navy was still segregated during the war, and racist attitudes and policies flourished. African Americans were only allowed to serve as mess attendants and their duties included washing dishes, shining shoes, laundering clothes, and tidying rooms that belonged to officers. During meals, only white people were permitted to sit at tables in the mess hall; black enlistees ate in a small pantry where they were not even given chairs - they had to eat standing up, separated from their crewmates.

Phillips's first voyage onboard the Truxtun brought him to Iceland. When the destroyer docked, however, he could not go ashore because local authorities would not allow black recruits on Icelandic soil. In 1942, Phillips made a second trip aboard the Truxtun, this time to the island of Newfoundland, which lay off Canada's east coast. The destroyer departed Boston on February 15 and met up with two other vessels off the coast of Maine - the USS Wilkes, a destroyer, and the USS Pollux, a supply ship.

A fierce storm pelted the convoy as it steamed toward Newfoundland and forced all three vessels to go aground off the island's south shore in the early hours of February 18. Phillips, like most recruits, was sleeping below deck when the Truxtun ran aground. The force of the impact threw him from his bunk and sent him scrambling topside, where a giant wave almost washed him overboard. The coming hours were filled with panic and desperation. With their ship breaking up beneath them, the 156 men aboard the Truxtun had to somehow make it to shore in a raging winter storm. "I watched men being washed overboard with the waves and I watched men trying to swim and tossed on the rocks," Phillips later told author Cassie Brown, who wrote a novel about the disaster called Standing into Danger. (Tape 68, 4:06-4:16)

Still, Phillips, felt his best chance of survival was to leave the ship and head for a rocky beach, which lay about 250 yards from the Truxtun. A raft was about to depart for the coast and he decided to climb aboard. "I was talking to three other black messmen and one Filipino. They assured me that if I would get in the water I would surely die. I said I would not stay aboard a ship and freeze as I was covered with ice from the spray of the ocean. I could see the fence on top of the cliff after daybreak and I told them that there surely must be a village or farm beyond the cliff." (Tape 68, 4:40-5:22)

But his companions would not leave the destroyer - they were afraid that if they made it to town, the local white residents would lynch them. Undeterred, Phillips got into the raft and departed for shore, hoping the small vessel would somehow carve a safe path through the violent waters and jagged rocks that lay ahead. It was a terrifying voyage - icy waves, howling winds, and blowing sleet drenched Phillips's clothing, numbed his body, and drained his energy. When the raft finally made it to shore, Phillips collapsed onto the rocky ground - he desperately wanted to go to sleep, but knew that if he did, he would surely die. Instead, he and shipmate Harry Egner decided to follow some other sailors up the icy cliff. Phillips went first and helped pull Egner to the top. Once there, they found an abandoned hay shed and dilapidated fence, but no other sign of habitation. Freezing and desperate, the two men began walking in a direction they hoped would take them to civilization.

It did - in time, the two sailors met up with some men from the nearby mining town of St. Lawrence, who were on their way to the shipwreck site. Phillips was by now in a semi-conscious condition and only vaguely aware of what was happening. "I remember going over the cliff and seeing the shed, but it seems to me that just before I reached the village with the houses in sight I passed out and I recall someone putting me on a sled," he later remembered. (Tape 68, 7:03-7:24)

The sled took Phillips to Iron Springs Mine, which had been turned into a makeshift hospital by the St. Lawrence residents. Phillips fell under the care of Violet Pike, who bathed him in warm water and rubbed life and feeling back into his frozen limbs. Pike then took the exhausted sailor into her own home, where she and her family nursed him back to health during the night that followed. Phillips was stunned. Never before had white people treated him with respect and kindness, yet here he was, eating dinner with his white hosts, who clearly thought that his life was not only worth saving, but was no less important than their own. It was a moment of awakening for Phillips, who later said the humanity shown to him in St. Lawrence changed his entire philosophy of life - it gave him dreams and ambitions; it gave him a newfound sense of self-worth; and it made him realize that he could shape his own future.

Once Phillips recovered, he returned to the United States and began to fight the racial discrimination that had oppressed him since childhood. Tired of shining shoes and washing dishes as a mess attendant, Phillips decided to apply to the Navy's sonar school and become a technician. Change, however, would not come easily. The Navy rejected Phillips's application simply because he was black. Undeterred, Phillips continued to press for admission. He wrote Congressman Charles Diggs - the first African American elected to Congress from Michigan - and received from him a letter of recommendation. With a US Congressman on his side, Phillips was finally admitted to sonar school. Still, he received little support from his fellow servicemen and was even offered a bribe by a Navy counselor to abandon his studies - if he left sonar school, Phillips was promised a promotion to chief steward mess attendant. He declined and went on to become the Navy's first black sonar technician in 1957.

After 20 years of military service, Phillips retired from the Navy in 1961 and cultivated a successful civilian career in engineering and sonar technology. He worked as a civil technician for EG&G engineering firm, joined the ALVIN deep-water submersible team, and collaborated with famous marine explorer Jacques Cousteau to develop a deep-sea lighting technology known as the calypso lamp.

He also continued to fight racial discrimination and became active in the Civil Rights movement. In March 1965, Phillips joined Martin Luther King's historic 54-mile march from Selma, Alabama to the state's capital city, Montgomery. The demonstration encompassed three separate marches and its goal was to secure equal voting rights for African Americans. About 600 people joined the first march, which took place on March 7. However, they only walked six blocks before state troopers and local police assaulted them with clubs and tear gas. Two days later, King led about 2,500 people on a second march across those same six blocks as a show of solidarity and protest. Finally, on March 21, about 8,000 men and women assembled in Selma for a third march that would last five days and take them to Mongomery, Alabama; Lanier Phillips was part of that demonstration.

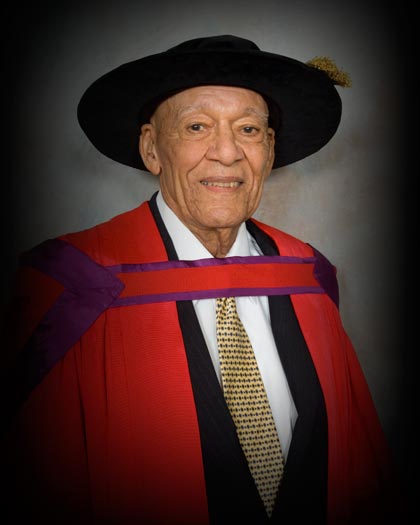

In the coming years and decades, Phillips continued to speak out against discrimination and oppression. He has travelled all over North America on numerous lecture tours and his audiences have included schoolchildren, university and college students, military personnel, and the public in general. He also stays in touch with the people of St. Lawrence, where a playground has been built in his honour. In May 2008, Memorial University of Newfoundland gave Phillips an Honorary Doctor of Laws Degree for his resistance to and capacity to rise above repression. Today, Phillips lives in Washington D.C. and is widely regarded as a hero and a civil rights role model. In St. Lawrence, Newfoundland, however, he is also known as a friend and a well-loved member of the community.

See also the September 16, 2010 Washington Post interview with Lanier Phillips. Two days earlier Phillips had received the U.S. Navy Memorial's Lone Sailor award for Navy veterans who had distinguished civilian careers.

Rescue and Recovery

Soon after 8:00 a.m. on the stormy Ash Wednesday morning of February 18, 1942, a dazed and semi-frozen American sailor named Edward Bergeron stumbled into Iron Springs Mine, near the small community of St. Lawrence, Newfoundland. His ship, the destroyer USS Truxtun, had gone aground with its crew of 156 men about three miles away in Chambers Cove. Upon hearing Bergeron's story, the Newfoundlanders shut down the mine for the day, sent word to St. Lawrence that help was needed, and set out for Chambers Cove with ropes, axes, blankets, and as much food as they could carry.

In the coming hours, these brave men of St. Lawrence risked their own lives to save strangers in imminent danger. They waded hip-deep into freezing waters and pulled dozens of men out of the ocean; they carried semi-conscious survivors over ice-covered cliffs; and they brought them back to Iron Springs Mine, which the local townsfolk had transformed into a make-shift hospital. There, St. Lawrence women bathed freezing sailors in warm water, dressed them in dry clothing, and fed them piping-hot bowls of soup and steaming cups of tea or coffee. Everything the men ate and wore had come from homes belonging to these women and their neighbours - food from their cupboards, clothes from their closets, and blankets from their beds. After the survivors were dressed and fed, they were bundled into trucks and carried away to various homes in St. Lawrence, where families took them in and cared for them all night long.

While the St. Lawrence residents were saving the Truxtun survivors, a second rescue attempt was unfolding about one and a half miles west at Lawn Point. There, another ship, the USS Pollux, had gone aground that same morning with its crew of 233 men. No one at St. Lawrence knew about the Pollux, but word reached the small fishing village of Lawn by about midday that a second vessel was in trouble. The wreck site was about a six-hour walk away - through 10 miles of thick woods and tall hills - but eight men set out with ropes and axes. When they arrived at sundown, about 122 survivors were trapped on an icy ledge at the base of a tall cliff and a couple dozen more were stranded in a cave further along the coast.

The eight men from Lawn quickly lowered a rope over the cliff and began to pull up survivors. Their hands became blistered and bloody from the work, but they continued into the night, desperately trying to pull up the remaining sailors before the small ledge disappeared beneath a rising tide. After a few hours, other rescuers arrived from St. Lawrence. Many were the same men who had spent most of the day saving Truxtun survivors in Chambers Cove. Tired and chilled to the bone from hours of backbreaking work, these heroic men did not hesitate to travel to Lawn Point when word reached St. Lawrence that a second vessel had gone aground. By dawn the following day, the men from Lawn and St. Lawrence had pulled more than 100 men over the cliffs at Lawn Point. All survivors were taken to Iron Springs Mine and then into the homes of St. Lawrence residents.

A total of 186 American sailors survived the Pollux and Truxtun groundings and all of them owe their lives in large part to the tremendous heroism and generosity displayed by the residents of St. Lawrence and the eight men from Lawn. To this day, the actions of those brave Newfoundlanders on that wind-swept Ash Wednesday in 1942 remain a testament to human courage and compassion.

For months after the disaster, local residents helped to recover bodies and body parts belonging to the 203 American sailors who died at Chambers Cove and Lawn Point. Many corpses were unidentifiable by the time they washed ashore or were found floating near the coast, and an indeterminate number were never recovered at all. Navy divers also pulled some bodies from the wrecked ships, but stormy seas delayed their work until the first week of March. Forty eight servicemen were buried at a cemetery in Argentia during the first week after the groundings and another 90 were buried at St. Lawrence in the coming months. Their bodies were exhumed and returned to the United States after the war.

1. Brooks, Chris, "The Survivor," http://www.batteryradio.com/Pages/Survivor.html

http://www.mun.ca/mha/polluxtruxtun/lanier-phillips/

No comments:

Post a Comment