1964 - America - Caucasian, Christian and Jewish young men and women from the northern American states travelled to Mississippi to encourage and help the Negro people there to register to vote.

Those young students left their families, their schools and their jobs to help simple strangers to stand up for what was rightfully theirs. A human right - to choose one's leaders.

The volunteers took their lives in their hands. Many of them were beaten, strip searched, imprisoned, and severely injured. Some of them were murdered.

In Mississippi, Negro people were frequently lynched - in our time. There was no penalty for lynching Negroes in a place where the government and the police were red-neck murderers. By day, they sat at desks, wore uniforms with badges and wielded clubs. By night, they wore white sheets and hoods and burned crosses and lynched anyone they pleased.

Slavery was formally ended, but the White people of the south were the slave owners, and sons and daughters of the slave owners. Their property - their slaves, the labourers and servants who built the wealth of America in the cotton fields - had been taken from them. They could do anything they wanted to Negro people and no one would stop them. Yes, It was America in the 1960's.

The dark skinned people of Mississippi outnumbered the slave owners. If the Negro people could vote, they could elect Negro leaders, Negro sheriffs, a Negro government. To prevent that nightmare, the White ladies and gentleman were ready to kill - and they did.

Now America has a president who is as much Negro as he is White. You might not agree with everything he does, but Barack Obama is the light of America. As president, he is proof that the blood shed by the innocent was not for naught.

But, to this day, I believe there is no "United States of America." Given the opportunity, the Republicans would bring back the Olde South.

Phyllis Carter

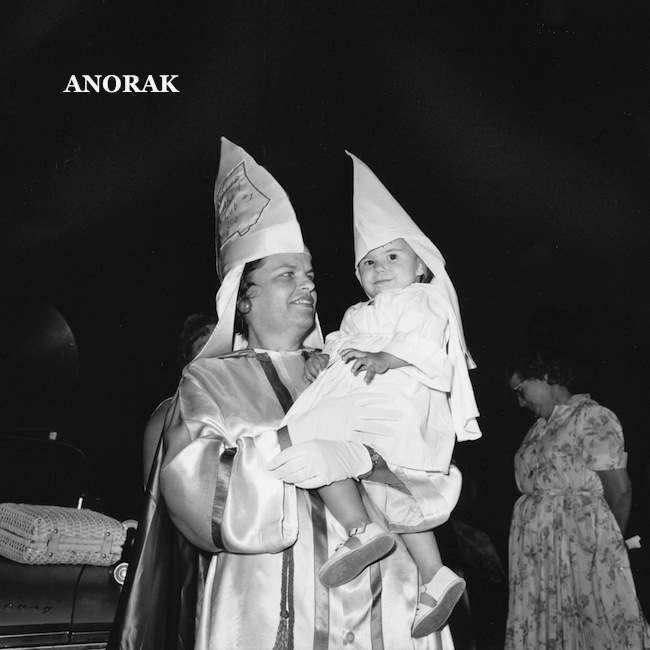

A member of the Ladies' Auxiliary of the United Klans of America, Inc., holds her young daughter, also robed in a Klan suit, at a Ku Klux Klan rally in Atlanta, Ga. on June 5, 1965. Some 600 persons attended the rally. The woman did not want to be identified. (AP Photo)

In this April 30, 2008, file photo Senate President Pro Tem Sen. Robert Byrd., D-W.Va., bangs the gavel on Capitol Hill in Washington prior to a joint meeting of Congress. Byrd, a former member of the Ku Klux Klan and a one-time opponent of civil rights legislation, is endorsing Barack Obama for the Democratic presidential nomination and says Obama has the qualities to end the Iraq war. In a written statement, Byrd called Obama "a shining young statesman, who possesses the personal temperament and courage necessary to extricate our country from this costly misadventure in Iraq." (AP Photo/Susan Walsh, File)

In 1964, civil rights organizations including the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) and Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organized a voter registration drive, known as the Mississippi Summer Project, or Freedom Summer, aimed at dramatically increasing voter registration in Mississippi.

The Freedom Summer, comprised of black Mississspians and more than 1,000 out-of-state, predominately white volunteers, faced constant abuse and harrassment from Mississippis white population. The Ku Klux Klan, police and even state and local authorities carried out a systematic series of violent attacks; including arson, beatings, false arrest and the murder of at least three civil rights activists.

http://www.history.com/topics/black-history/freedom-summer

When SNCC activist Robert Moses launched a voter registration drive in Mississippi in 1961, he confronted a system that regularly used segregation laws and fear tactics to disenfranchise black citizens. In 1962, he became director of the Council of Federated Organizations, a coalition of organizations led by SNCC that coordinated the efforts of civil rights groups within the state. Capitalizing on the successful use of white student volunteers in Mississippi during a 1963 mock election called the ''Freedom Vote,'' Moses proposed that northern white student volunteers take part in a large number of simultaneous local campaigns in Mississippi during the summer of 1964.

Letters to prospective volunteers alerted them to conditions in Mississippi, explaining the likelihood of arrest, the need for bond money and subsistence funds, and the requirement that drivers obtain Mississippi licenses for themselves and their cars. Volunteers were also asked to prepare for the experience by reading several books, including King's memoir of the Montgomery bus boycott, Stride Toward Freedom, and Lillian Smith's novel Killers of the Dream.

On 14 June 1964 the first group of summer volunteers began training at Western College for Women in Oxford, Ohio. Of the approximately 1,000 volunteers, the majority were white northern college students from middle and upper class backgrounds. The training sessions were intended to prepare volunteers to register black voters, teach literacy and civics at Freedom Schools, and promote the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party's (MFDP) challenge to the all-white Democratic delegation at that summer's Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Just one week after the first group of volunteers arrived in Oxford, three civil rights workers were reported missing in Mississippi. James Chaney, a black Mississippian, and two white northerners, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, disappeared while visiting Philadelphia, Mississippi, to investigate the burning of a church. The abduction of the three civil rights workers intensified the new activists' fears, but Freedom Summer staff and volunteers moved ahead with the campaign.

Voter registration was the cornerstone of the summer project. Although approximately 17,000 black residents of Mississippi attempted to register to vote in the summer of 1964, only 1,600 of the completed applications were accepted by local registrars. Highlighting the need for federal voting rights legislation, these efforts created political momentum for the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In an effort to address Mississippi's separate and unequal public education system, the summer project established 41 Freedom Schools attended by more than 3,000 young black students throughout the state. In addition to math, reading, and other traditional courses, students were also taught black history, the philosophy of the civil rights movement, and leadership skills that provided them with the intellectual and practical tools to carry on the struggle after the summer volunteers departed.

At Mose's invitation King visited Greenwood, Mississippi, to show the support of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference for the summer project and to encourage black Mississippians to vote despite acts of violence and intimidation. Less than three weeks after King's visit, the murdered bodies of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were found. King characterized their brutal deaths as ''an attack on the human brotherhood taught by all the great religions of mankind'' (King, 4 August 1964).

Freedom Summer activists also worked to make the MFDP a viable alternative to Mississippi's ''Jim Crow'' democratic convention delegation. King publicly supported the MFDP, telling the 1964 convention's credentials committee, ''if you value your party, if you value your nation, if you value democratic government you have no alternative but to recognize, with full voice and vote, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party'' (King, 22 August 1964). While the MFDP was initially unsuccessful, some of its members were seated at the 1968 convention.

Freedom Summer marked one of the last major interracial civil rights efforts of the 1960s, as the movement entered a period of divisive conflict that would draw even sharper lines between the goals of King and those of the younger, more militant faction of the black freedom struggle.

SOURCES

Carson, In Struggle, 1981.

King, Statement before the Credentials Committee, 22 August 1964, MLKJP-GAMK.

King, Statement on the deaths of Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney, 4 August 1964, MLKJP-GAMK.

Martinez, Letters from Mississippi, 1965.

No comments:

Post a Comment