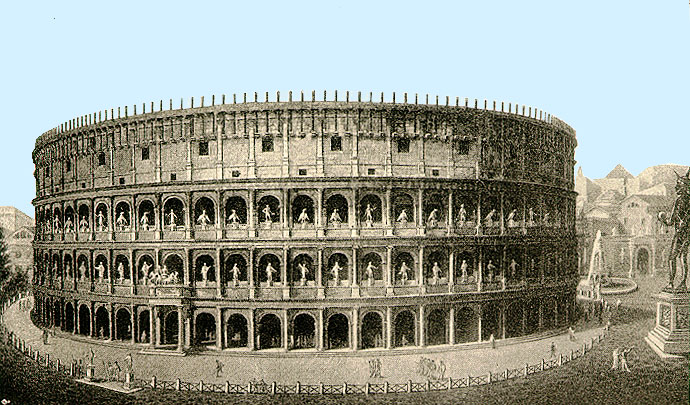

Oh, how tourists love to visit the Roman ruins !

What magnificent buildings !

Does anyone stop to think?

Here,

Thousands of enslaved human beings,

And helpless animals,

Were slaughtered -

To echoing cheers and applause.

Here

There is blood and tears.

Here

Tortured souls scream out to be remembered.

These places are not glamorous.

Like the concentration camps of Germany,

These places are tragic graves !

The blood baths enjoyed here

By the savage Roman people -

Outrageous !

By the savage Roman people -

Outrageous !

Phyllis Carter

Like chariot racing, contests of gladiators probably originated as funeral games; these contests were much less ancient than races, however. The first recorded gladiatorial combat in Rome occurred when three pairs of gladiators fought to the death during the funeral of Junius Brutus in 264 BCE, though others may have been held earlier. Gladiatorial games (called munera since they were originally "duties" paid to dead ancestors) gradually lost their exclusive connection with the funerals of individuals and became an important part of the public spectacles staged by politicians and emperors. The popularity of gladiatorial games is indicated by the large number of wall paintings and mosaics depicting gladiators; for example, this very large mosaic illustrating many different aspects of the games covered an entire floor of a Roman villa in Nennig, Germany. Many household items were decorated with gladiatorial motifs.

GLADIATORS:

Status: Gladiators (named after the Roman sword called the gladius) were mostly unfree individuals (condemned criminals, prisoners of war, slaves). Some gladiators were volunteers (mostly freedmen or very low classes of freeborn men) who chose to take on the status of a slave for the monetary rewards or the fame and excitement. Anyone who became a gladiator was automatically infamis, beneath the law and by definition not a respectable citizen. A small number of upper-class men did compete in the arena (though this was explicitly prohibited by law), but they did not live with the other gladiators and constituted a special, esoteric form of entertainment (as did the extremely rare women who competed in the arena). All gladiators swore a solemn oath (sacramentum gladiatorium), similar to that sworn by the legionary but much more dire: "I will endure to be burned, to be bound, to be beaten, and to be killed by the sword" (uri, vinciri, verberari, ferroque necari, Petronius Satyricon 117). Paradoxically, this terrible oath gave a measure of volition and even honor to the gladiator. As Carlin Barton states, "The gladiator, by his oath, transforms what had originally been an involuntary act to a voluntary one, and so, at the very moment that he becomes a slave condemned to death, he becomes a free agent and a man with honor to uphold" (The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster [Princeton University Press, 1993] 15). Trained gladiators had the possibility of surviving and even thriving. Some gladiators did not fight more than two or three times a year, and the best of them became popular heroes (appearing often on graffiti, for example: "Thrax is the heart-throb of all the girls"). Skilled fighters might win a good deal of money and the wooden sword (rudis) that symbolized their freedom.

Freed gladiators could continue to fight for money, but they often became trainers in the gladiatorial schools or free-lance bodyguards for the wealthy.

Freed gladiators could continue to fight for money, but they often became trainers in the gladiatorial schools or free-lance bodyguards for the wealthy.

No comments:

Post a Comment